The practice of calling the mind back, when it has wandered off somewhere is called ‘pratyahara’ in Patanjali’s yoga sutras, an ancient work on how to meditate for the purposes of spiritual advancement. We know now that there is neuroscience behind Yoga and Meditation: the ancient practices of Patanjali do impact our cognitive and behavioural functions, and there is proof in laboratories all over America and the UK for such claims.

The West is getting wise to this, using their own methodology – the scientific method of controlled trials. We know for example from Sara Lazar’s research at Harvard that meditating for a short time will cause structural alterations in the brain. Meditation has been shown to slow down atrophy – keeping us young. It should be part of the mainstream core skills, it is argued.

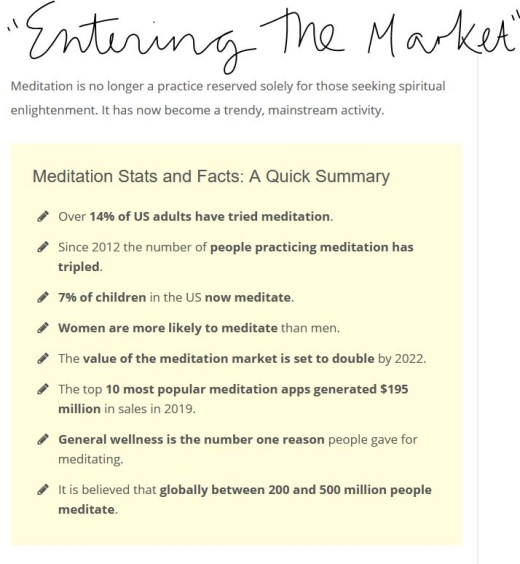

Business has clocked into these findings, and now at the click of a button, there is an app to download on our smartphones, for practising meditation. Millions are being made on the back of these apps.

What we know also from the Oxford Meditation Centre’s work that providing resources for practitioners is a huge part of making this practice enter the mainstream.

A medical interest in mindfulness practice

Their interest in this was originally discovering that practicing mindfulness has a major impact on recovery from depression, and avoiding future episodes of depression in those diagnosed with the condition.

Mindfulness research in Oxford shares a vision I am sure, with many doctors and psychologists who struggle with patients who are suffering from depression and related disorders: ‘A world without the devastating effects of depression where people live with understanding, compassion and responsiveness.’ They have also started to explore Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy’s acceptability and effectiveness in different settings, such as teachers working in schools and prisoners in the criminal justice system.

Helping young people of school age

In this they are working alongside the Mindfulness in Schools Project. Meditation is not just a medical remedy. It is actually a great aid to life in general and learning in particular. They are saying that ordinary people should learn to meditate from an early age, in order to learn better, to manage their emotions with a bit more confidence, and make more informed life choices.

How meditation can improve learning and memory, and help with decision-making processes is best covered by the evidence page of the Mindfulness in Schools Project’s research, evidence and case studies page.

They have a hub for teachers who are already qualified, supporting their work with papers and group work.

Should spiritual practitioners help this practice of pratyahara to become even more mainstream?

Patanjali sees meditation as the core skill for conducting a spiritual quest in a private capacity in any religion – a number of world religions have meditation as their core curriculum, but both Vivekananda (and Patanjali for all I know), are indifferent as to the exact religion of the person practising meditation. The composition of the human being is the same, and the rules of mastery remain the same too. Thakur was certainly here to demonstrate that the individual’s focus can be on any religion. He did not mind which one suited the practitioner best. He taught general principles.

Does the saffron robe get in the way of teaching core skills?

What a nineteenth century monastic order like the Ramakrishna Mission does not aim to do, is facilitate the entry of meditation into the modern skills base of every economy – without any reference to spiritual advancement. Spiritual advancement of the individual is actually its stated aim – self realisation or God realisation, which are known by the Order to be the same, is the ultimate goal of human life, and it is their mission to bring a sense of urgency into the spiritual lives of individuals seeking their personal spiritual goals. As I have seen them, these are highly educated people who have mastered the teaching of meditation to their own novices and monks. They have also taken every opportunity to teach their monks how to do their work in the self-less detached way which constitutes karma yoga.

Is spiritual practice an effective aim for a world movement for pratyahara?

In practical terms however, in a world where a very small percentage of people are interested in spiritual life, the way to make meditation (and in particular pratyahara) a widely practiced skill would be to say nothing about the spiritual work which one can do, but to emphasise the ‘quality of life’ issue.

This would be desirable social enhancement project for the benefit of all mankind. It is also the preparatory step for creating a pool of people in different walks of life who have this basic skill of pratyahara – the ability to notice where the mind has gone, and call it back to a desired place (during meditation, to the chosen focal point, and during work, to the task in hand).

Every employer, in whatever industry or service provision, should be keen to hire a young person who meditates – they will simply be more capable of concentrating on, and finishing whatever work they started.

It should be seen as way of ‘creating capacity’, not only for effective employees of large organisations, but also of effective searchers for individual salvation, while living to serve humanity.

This would be a good pool of people who would support the monastic order of Sri Ramakrishna, which sits on the common ground between all religions, (and holds pratyahara high in it’s toolbox of skills for all those who would wish to join the order).

Therein lies the possibility of an end to all religious wars. It might also turn out to be a good bit of long term planning for the Order. From such a pool of people would come the parents who would allow their boys and girls to become monks and nuns of this unique order, so this level of service to mankind can be maintained.